Ambition

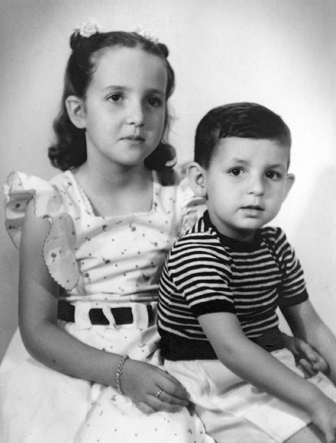

Esther Tusquets. Publisher and writer. Barcelona, 1936

Under the entry for “ambition” the Diccionario de la Real Academia Española reads: ardent desire to achieve power, wealth, distinctions or fame. The only relevant part here is ardent desire, because the objects of desire that are listed are, if not misguided (there is no denying that most human beings covet power, distinctions and fame and, more generally still, wealth), at least, insufficient. What about the desire to change the world, to improve the lot of humanity, to open up new paths in science, to create individual and enduring works, to be universally loved? If this is not ambition, what name shall we give it? I can think of none. Was not Christ enormously ambitious in trying to establish among men a new order based on love? Could anybody imagine that Mi-chelangelo, as he painted the Sistine Chapel or sculpted the tomb of the Medicis, was thinking first and foremost only of the distinctions he would receive from the Pope, the money he would be paid by the Dukes, or how his fame would grow? / Ambition written in capital letters, that great ambition which needs no justification and which I would attribute to Oscar Tusquets, has two cha-racteristics. First, it never allows him to feel fully satisfied with his achievements, or at least not for very long, which condemns him to a certain degree of dissatisfaction and to feelings of failure. Second, it is incompatible with vanity. These two things occur in inverse proportion to one another. The more genuine one’s ambition, the less time and room it leaves for vanity, and unbridled vanity does irreparable damage to one’s ambition. (Marguerite Yourcenar wrote that, as a little girl, she aspired to glory, but glory and immortality should not be confused with fame, which is always ephemeral.) / When he was ten years old, Oscar wanted to be a carpenter, and he ardently strove for the same degree of perfection in his furniture. When he was fifteen, Oscar wanted to be Michelangelo, another Michelangelo (I think, both because of his extraordinary, passionate nature and the greatness of his works), which brings us up to the present. It would be wrong to think of this as vanity. In our family, we were brought up to respect precision and rigour, to respect the work in hand, whether it be a bedside table or a cathedral, executed to the best of one’s ability, and we were brought up, above all, to feel absolute contempt for vanity and, in particular, ostentation, which was always regarded as something vulgar and ridiculous. (It is significant that Oscar’s most recent book deals with those elements of a work of art that the public at large can never see: visible only to God, or, I would add, to oneself.) / Oscar Tusquets may be prey, indeed he is prey, to many small, absurd vanities, which are not always easy to explain and cause dis-appointment (sometimes ingenuous and sometimes malicious), but never in relation to what really matters to him, as indeed to all of us, which is his work. Perhaps it is because he is not vain in this respect that he is not envious either, a rare quality in the world we live in: if he feels someone else’s work to be mediocre, he does not envy the fame, distinctions and money that those works bring their author; if he thinks that the work is interesting and valuable, he whole-heartedly enjoys and ad-mires it without reservation. I have never heard him utter a mean, petty comment. / In a sense that goes unrecorded in the Diccionario de la Real Academia Española (who knows who wrote the definition), Oscar Tusquets is a genuinely ambitious man, ambitious with a capital A, ambitious in the noblest and most committed sense of the word.

Esther and Oscar. Photograph Studio, 1946